Welcome to the 193 new readers who have joined since the last article! If you aren’t already subscribed, join the community of 2,183 investors by subscribing below.

My aim with these deep-dives is to make the research process accessible to everyone. So far I have ‘deep-dived’ into over 30 growth companies such as Coupang, Disney, Snapchat, Nio, Spotify, Shopify, Netflix, Nvidia, , MercadoLibre, Roku and many many more.

If you would like to donate, please do so by following the button below :)

You can find me on twitter @innovestor_. DM’s are always open.

Enjoy!

Contents

Thesis

Key Takeaways

Background

Business Model Overview

Market opportunity

Competition

Management

Bull Case

Bear Case

Financials

Conclusion & Future vision

Intro

Uber is a company dividing opinion. Some see it as a future trillion dollar company, whilst others see a mess-of-a-company struggling to figure out it’s business model.

In this deep-dive, I will do my best to outline the good as well as the bad around Uber’s business-model and give my opinion on what this will mean for the future of the company as well as the stock.

1. Thesis

Uber sits nicely in the small group of companies I like to call ‘verb stocks’. By this I am referring to a situation where a brand name has edged its way into our everyday vocabulary, resulting in what is basically free marketing for the respective companies.

Good examples of such ‘verb stocks’ include Google (“google it”), Zoom (“Lets Zoom this afternoon”) and DocuSign (“Can you DocuSign the contract?”) etc.

This alone doesn’t create a compelling thesis to invest in the company - there are plenty of examples of companies who were once used in a similar way but we no longer use.

Over and above this initial observation, Uber is a pioneer of the gig-economy. They offer a well used and (mostly efficient) product that has quite literally paved the way for a whole host of other gig-economy/freelance companies. One of the best things to come from modern tech, and more specifically Uber, is that if you want to earn a bit of extra money on the side, you can.

Lastly, Uber has some incredibly valuable underlying assets that engulf many different industries - mobility, food delivery, transit and Autonomous Vehicles. These businesses on their own could be incredibly valuable businesses. The real kicker is how valuable these businesses will be when they converge into one delivery/travel super app by leveraging the unique and vast two-sided network the company has been building over the past decade.

Uber are creating serious momentum at the at the moment from all areas of the business. All of this at what looks a reasonable price compared to other big tech.

All this being said, I’m torn on the stock as it stands. The extreme market competition, poor unit economics, lack of path to profitability and continuous cash burn are signs of a company that will continue to struggle in the future.

In this deep dive I will try to tell both sides of the story, hoping you will find this a useful data-point in coming to your own conclusion on the stock.

2. Key Takeaways

General points

Optionality is staggering and Uber are continuously adding. The new(ish) Ads on Eats could be a huge opportunity (potentially over 70% gross margin). "Our original goal was to exit this year with $100M of Ads run-rate revenue, but we now expect to surpass that goal and end 2022 with at least $300M in run-rate revenues"

Continued growth in other aspects of the business including Eats and Freight.

"Freight has successfully disrupted the freight brokerage market with our innovative technology, and is now one of the largest digital freight brokers globally excluding China"

"Our acquisition of Postmates has helped us establish Eats as a #1 position in LA, the second largest Delivery market in the US, while allowing us to execute organically to establish category leadership in NYC at the same time"

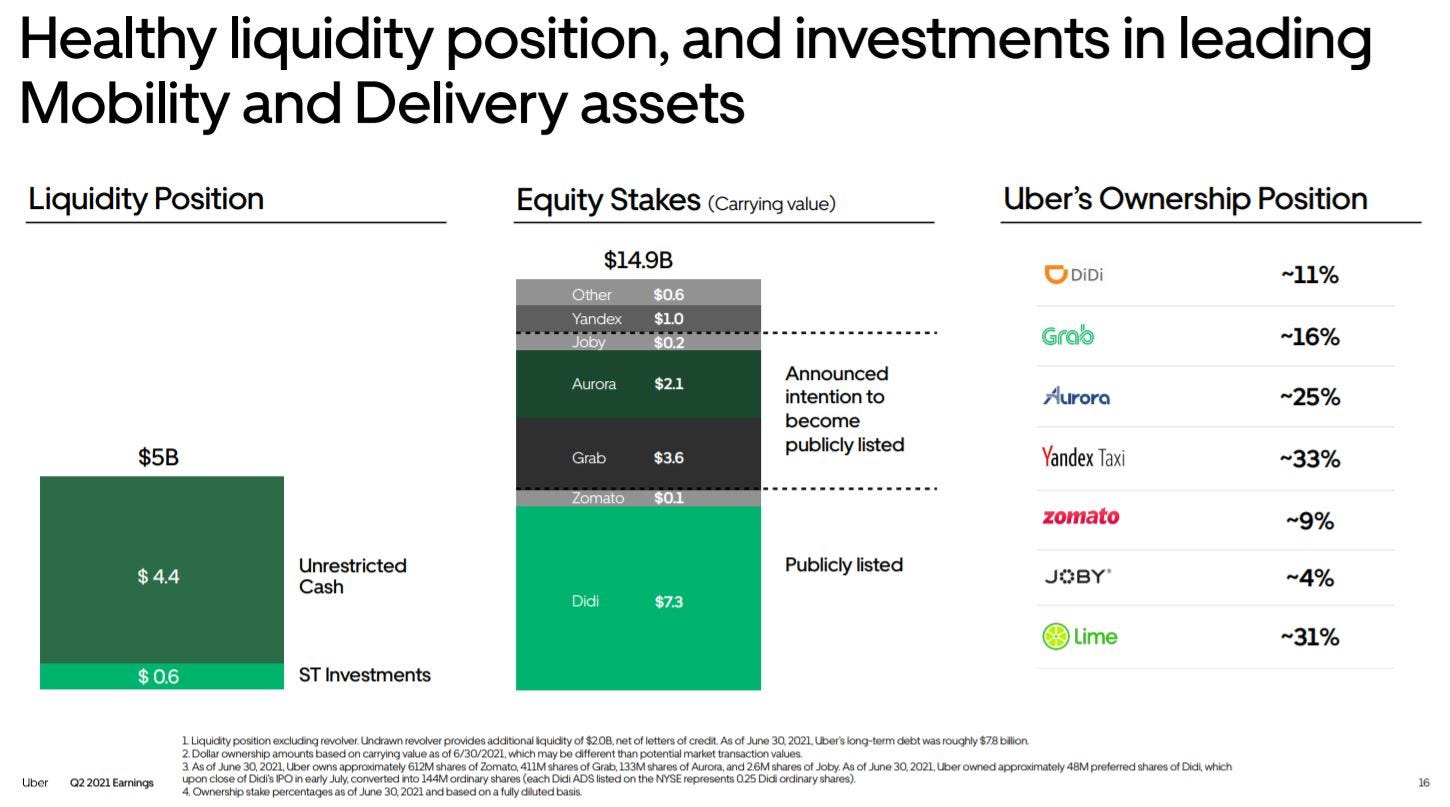

Total of $20B in liquid and equity stakes - for reference, “Q2 ‘profit’ was mainly driven by the unrealized gain in having a stake in Didi as well as a $471m Unrealized gain on their Aurora investment.”

Improving driver churn with ‘Uber Pass’ - "..the retention rate for our cohorts that are with us more than six months is now 98% retention rate on a month-on-month basis."

Path to profitability is uncertain.

Unit economics look poor.

Q2 2021 highlights

Active drivers up 75% y/y, new drivers up 30% MoM even as incentives are being tapered.

Eats is driving user acquisition for rides. “+20% of mobility’s first time riders in the US and +40% of first time riders in the UK were existing Delivery consumers”.

Uber are locking in their most loyal customers with their subscription product, Uber Pass. "drives 30% of Delivery GBs in the US, and roughly 25% globally. Consumers who regularly engage with both Mobility and Delivery now account for nearly half of our total company GB"

Uber Eats continues to grow their market share. "And our leadership position continues to grow. We are now the category leader in 8 of our top 10 Delivery markets, with clear #2 positions in the US and UK"

Incentives likely to stay high in Q3

3. Background

Uber was founded in 2009 by Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick with the name ‘UberCab’.

The idea for Uber was built on the personal experiences of the co-founders. Allegedly on New Years eve of the previous year, Garret Camp spent over $800 dollars on a private car service, which then inspired him to come up with a more affordable solution to private-hire transport.

After significant market research, Camp and Kalanick hired technical experts to determine if the project had legs. Following this, the first Uber ride was undertaken in 2010 in San Fransisco.

The company continued to develop other similar products such as UberX, UberBlack and UberPool - with eventual expansion into the food delivery market in 2014 - to later be known as Uber Eats.

Fast forward to 2021 and Uber are continuing to add more strings to their bow, with Uber Freight, ATG, some micro-mobility plays and much more.

4. Business Model Overview

At it’s core Uber is a matchmaker for those seeking a service, and those providing it. Originally, this manifested in the ride-sharing app, but quickly expanded into other verticals such as food and trucking. There are probably too many aspects (established and emerging) to cover in this one article, however lets go over the main ones - rides, deliveries, Freight and ATG, exploring some of the unit economics at play.

4.1 Moat

But before all of that, lets talk about the moat and what makes Uber unique.

At the very core of Uber’s business is a very robust and hard to replicate two-sided network of drivers and passengers. In a traditional taxi market, there can only ever be a certain number of taxi’s at any given time. This puts a cap on supply therefore forcing prices up and increasing wait times.

The more liquid one side of the market is, the more valuable it is to the other side.

This two-sided network has grown significantly over time to become the largest global network of drivers and users.

Part of the ‘moat’ here is the difficulty for any one company to easily replicate what Uber do - expanding into most major cities in the world is not an easy, quick or cheap thing to do. They have also been met with significant local blockers such as the disruption of local taxi businesses.

On the other hand, one of the business model’s great drawbacks is the inherent ‘physical’ nature. For example, if your modern online tech giant such as Facebook or Snapchat wanted to expand into Germany, it’s a relatively simple process with almost 0 extra cost associated. However, Uber on the other hand need to have a physical presence in every city they expand to. This includes developing infrastructure by inspecting cars, running background checks, creating a two-sided marketplace where there was none previously - the list goes on. Physically scaling has always been an issue for Uber.

Above and beyond the ridesharing segment of the business, the moat for the wider business is the synergistic nature of the different arms of Uber. Drivers will typically deliver for Uber Eats if the opportunity arises, and vice versa.

“…+20% of mobility’s first time riders in the US and +40% of first time riders in the UK were existing Delivery consumers”.

The end goal here is to create one ‘super app’ - combining and converging the various vectors into one efficient delivery service (rides, eats, freights, smaller mobility, stakes in other ridesharing companies, potential for AV in the future, Uber pass, Uber for business, more high-margin/kg deliveries such as cannabis/alcohol/other high-ticket items).

If you are willing to think outside the box and are comfortable waiting a long time, this future seems very plausable.

4.2 Broad strategy

As hinted above, the overarching strategy here relies on becoming/remaining the dominant player in each of the mentioned verticals - eventually creating a delivery super app. I think their mission statement puts it nicely…

Mission Statement:

“Transportation as reliable as running water, everywhere for everyone.”

Increasing liquidity by integrating various modes of mobility into one app is a long-term goal for the company. I strongly believe this aspect will be key to the eventual success or failure.

According to the 2020 Annual Report (page 5): “over 56% of first time delivery consumers were new to our platform. Consumers who used both mobility and delivery generated 11.1 trips per month on average, compared to 5.1 trips per month on average for consumers who used a single offering in cities where both Mobility and Delivery were offered.”

Both drivers and customers will benefit from increased liquidity. It opens up more future revenue potentials and cost saving efficiencies than close competitors such as Lyft who just focus on mobility.

Now, lets focus on several segments (Mobility, Delivery and Freight) - diving into how they work and how they make (or lose) money.

4.3. Mobility

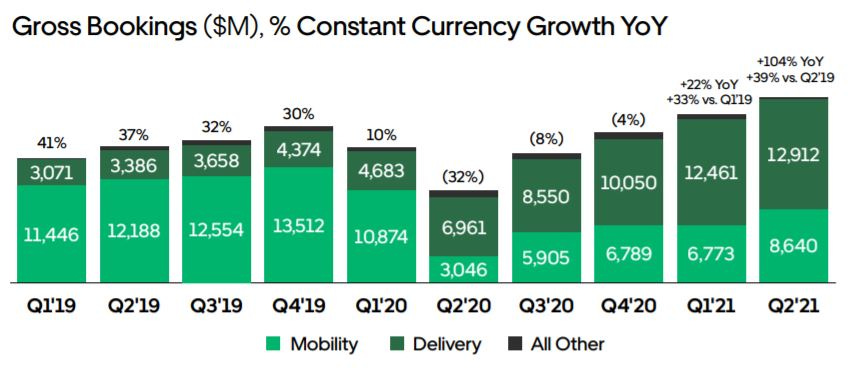

‘Rides’ is (was) the bread and butter of Uber’s business model. It is the original idea making Uber the multi-billion dollar company it is today. The global pandemic almost completely wiped out this aspect of the business, with Q2 2020 being the peak of the pandemic. Since then, recovery has been steady, but mainly driven by the eats segment.

The idea of a marketplace of drivers getting you, the customer, from A to B was an extremely innovative and disruptive idea at the time. The trouble was that Uber ended up with some bad press due to the displacement of the traditional taxi industry - essentially showing the taxi industry that they were not safe.

As someone who is personally ‘pro-innovation’ and ‘pro-disruption’, I think this shift to a new business model is an overall net benefit. Change happens in every industry. That being said, there are still substantial question marks around the treatment of the drivers.

Business model hinges on paying drivers as private contractors.

Uber don’t own their own cars, therefore no physical assets.

Historically unprofitable.

The question is, how does this business model work on a unit basis? Does the company actually make any money? And is it scaleable in order to achieve profitability over the longer-term?

Lets take a look.

4.3.1. Mobility Unit Economics

The fee Uber takes from its driver’s gross booking figure (per ride) varies and is dependent on market conditions and any incentives/surge pricing introduced by Uber at any given time.

Jalopnik asked ride-hailing drivers to share fare receipts, and it received data from more than 14,756 real-world trips in response. On average, Jalopnik, found, Uber kept about 35% of the revenue from each ride, and Lyft kept about 38%.

So, if we use that figure of 35% revenue retention from the gross booking, we can work out the level of profitability per trip.

One other thing to note is that Uber frequently offer incentives for drivers in order to retain a high level of market share. This tactic obviously eats into the short-term profitability with the hope of longer-term market share dominance. For example, on a $10 trip, the passenger might have a $3.50 voucher to use. If this is the case, then the driver would still take 65% of the $10 ($6.50) whilst Uber end up essentially ‘writing off’ any potential revenue.

If the level of incentives exceeds the total value of the trip, then no revenue is captured on the income statement. Any excess incentives are captured as costs of revenue.

The take rate is calculated as the adjusted net revenue divided by the Gross booking value (cost of ride). As we can see from the example above, take rates can vary wildly depending on the level of incentives Uber introduce at any given time.

The trouble for Uber is the fact that they rely heavily on these driver/user incentives in order to drive useage/loyalty in newer cities. It’s an essential aspect in the company’s growth and their ability to create substantial network effects.

Part of Uber’s problem here is the fact that users of ride-sharing apps don’t really tend to have much loyalty or care about which service they are using.

Only 34% of customers use both Uber and Lyft

2/3 of drivers drive for both apps

68% of drivers stop driving within 6 months

Churn levels are reported to be as high as 96% after 1 year

So, if Uber suddenly stop with the incentives & offers, they may also end up giving up significant market share. Therefore I raise the question of whether this model is sustainable long-term, especially with potential regulations in top Cities (where the majority of revenue comes from).

One other thing to add here is earlier in the year, Uber changed their stance on the employment rights of their drivers to be classed as ‘workers’, not employees. This could have significant unit cost implications if the trend were to continue in other large territories.

4.4. Uber Eats

Uber Eats is a relatively new aspect to the business having been first established in 2014 and is now the fastest growing division within Uber - making up 52% of total revenue for the first half of the year compared to 27% for the same period in 2020.

The success is mainly due to the fact Uber had the ability to draw upon its existing global network of drivers, leveraging the already available liquidity. This has worked in their favour in many locations where delivery networks were not already established - they had drivers at the ready.

A quick summary of eats:

Cost savings from using existing uber drivers

Couriers get paid a base fare + any tips + incentives/promotions

Charges restaurants $350 activation fee + 15% to 30% fee to use the platform

The segment remains unprofitable.

4.4.1. Uber Eats Unit Economics

Uber Eats generates revenue in 3 main ways:

a delivery fee from each customer

a percentage of each driver’s gross fare

and a 30% fee from the restaurant on each order

Similar to its Uber Pool service, Uber also bundles orders together, allowing couriers to deliver multiple orders from restaurants in the same area. The reason for this is to help reduce delivery fees, manifesting in promotions such as $0 delivery fees.

An Uber Eats order flow is fairly inefficient with many touch-points and several different stages…

Stage 1: Order

First you open the app and order your desired meal (lets go with a meal that comes to $25).

Tax, service, and delivery fees are then applied.

Any promotion is then deducted at the end.

From this point, the restaurant receives about 70% of the total booking value. This number can vary, but lets use 70% as an example.

The remaining 30% goes towards Uber, which is recorded in the income statement as revenues.

Stage 2: Delivery

The restaurant makes your meal.

Once ready, a nearby driver will accept the meal.

Driver drives to restaurant, waits for the food to be ready.

This driver will be paid a base fare + any tips + incentives. * Note, the driver only gets paid for the time travelling from the restaurant to the final destination. All the waiting time (dead-head time) is unpaid. Not super efficient for the driver*

Your order arrives. If you choose to tip, it all goes to the driver.

Here’s an example of a $25 order and how this flows through to the income statement…

Similar to the rides aspect of the business, the unit economics seem fragile. Uber will need to keep an eye on the incentives used over the long-term with the aim to reduce incentives in order to improve take-rate.

4.5. Growth and expansion

Growth in the food delivery sector is wild, especaially since Covid. The past several year has seen the major players in the industry attempt to consolidate their position by method of acquisition. Uber attempted to purchase Grubhub but failed, leading to JustEat learning from their mistakes and making the purchase in June 2020.

Uber did end up increasing their position in the market after acquiring Postmates shortly after in September 2020.

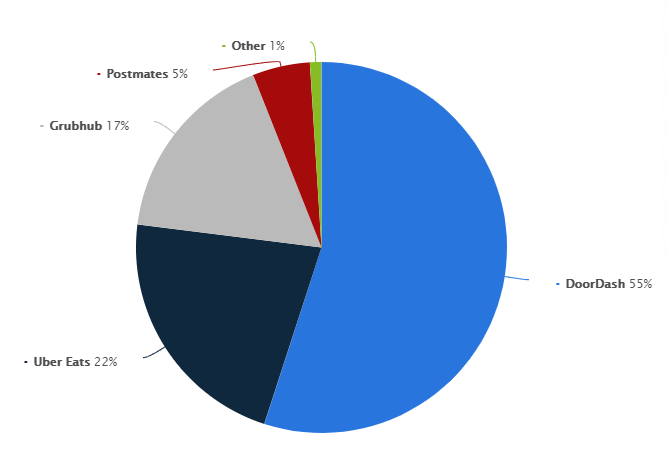

In the US, DoorDash remains the largest competitor in the US with 55% market share, up 5% from 1 year ago. uber takes second place with 22% followed by GrubHub with 17% and Postmates with 5%.

This desire to expand their food delivery network isn’t new. They recently acquired Cornership (LatAm, US & Canada).

The real question lies on the side of unit economics and whether the company can make this business profitable in the long-term. Rising costs for drivers, customers and restaurants raises big question-marks around viability.

4.6. Freight

Uber entered the market in 2007 offering Uber Freight - a marketplace connecting couriers and truck drivers with shippers. This allowed for up-front and transparent pricing.

Trucking is a big business, moving roughly 70% of all goods in the united states. However the business has always had problems with inefficiencies and has been slow to digitize over the past decade.

It can take several hours, sometimes days, for shippers to find a truck and driver for shipments, with most of the process conducted over the phone or by fax. Procurement is highly fragmented, with traditional players relying on local or regional offices to book shipments. It is equally difficult for carriers to find and book the shipments that work for their businesses, spending hours on the phone negotiating pricing and terms. These inefficiencies adversely impact both shippers and carriers, and contribute to the number of non-revenue or “dead-head” miles, which are miles driven by carriers between shipments.

Today, the Freight sector of the business reports over 70,000 trucking companies on its network which have access to more than 700,000 truck drivers. Some of its clients include Inbev, Nestle and Heineken. Q2 of 2021 saw Uber Freight bring in its highest ever gross bookings of $348M - a 64% increase Y/Y.

The below video is a good discussion on Uber Freight and logistics.

Again, the company is following a similar playbook for growth as they do in their mobility and deliveries segments - by sacrificing short-term profitability for longer-term growth.

As of october 2020, New York-based private equity firm Greenbriar Equity Group are to invest $500 million in its logistics arm, Uber Freight, valuing the unit at $3.3 billion on a post-money basis

4.7. ATG (Advanced Technologies Group)

“The ATG segment is primarily responsible for the development and commercialization of autonomous vehicle and ridesharing technologies.”

As of December 2020 Uber reached an agreement with Aurora Innovation, who are backed by Sequoia Capital and Amazon. The deal was reportedly complex, but ended up with Uber handing over its equity in ATG and investing $400M into Aurora - giving Uber a 26% stake in the combined company. Most importantly however, Uber CEO Dada Khosrowshahi will be taking a board seat in Aurora.

For reference, Aurora, which was founded in 2017, is focused on building the full self-driving stack - the underlying technology that will allow vehicles to navigate highways and city streets without a human driver behind the wheel.

The reason this is significant is because now Uber have skin in the game with regards to the race to create world leading AV technology, without being a main competitor for other AV companies like Waymo.

The big risk is that if another company manages to create the technology first, Uber will be beholden to whoever licences the technology. Realistically, however, the Autonomous Vehicle companies would need to partner with Uber and/or Lyft because they would face the exact same problem Uber currently has - too much demand for their supply. Uber and Lyft will be able to fill in this gap.

And more to the point, these AV companies will likely follow the money.

Beyond Uber’s focus on autonomous driving, the company is also looking into arial ride sharing as an alternate mobility method via the Uber Elevate business. Uber has subsequently done a similar deal with Joby to the ATG deal - giving Uber exposure to the idea but with reduced risk.

Elevate has already experimented with aerial transportation via Uber Copter, a helicopter service launched last year to fly passengers between lower Manhattan and JFK Airport.

4.8. Is AV technology good or bad for Uber?

After reading through tonnes of material on Uber and Autonomous Vehicle technology, it seems unclear to me exactly whether it’s something to look forward to as a shareholder or whether it’s the beginning of the end. It’s too early to know.

One thing we can say for certain is that the companies spending money in this space are throwing large amounts of cash at this thing. Because of this fact, it is very likely some company other than Uber beats them to a breakthrough. What would the economics of this particular situation look like for Uber I wonder?

The argument in favor of Autonomous Vehicle technology integrated into the Uber product offering is fairly straightforward to see from an outside perspective. The ability to have the same output (get a passenger or food item from A to B) but with significantly improved unit economics means Uber could transition from a loss making company to a profit making company essentially overnight.

However, is this really true? Say we simply eliminated the cost of revenues from the income statement in 2020 (as we no longer pay any drivers), Uber would just about be breaking even.

The real question is this - lets say one of the rivals (Waymo for example) gets there first, what is stopping them from creating their own app loaded with $100m worth of incentives in order to pull Uber users over to the new Waymo-ride app? Especially considering the fact that, as we know, neither drivers or customers within the ride-sharing economy are particularly loyal - they will follow the cheapest/most efficient option.

Having said that, my counter would be the fact that there is a reason there is a ride-sharing duopoly in the US when creating an app is so simple… It’s because acquiring and establishing high engagement rates in a large userbase is super expensive and a non-trivial customer acquisition exercise.

Therefore, in my opinion, even if the competition get to autonomous vehicle technology first, Uber still has the trump card of a global network of drivers and customers willing and ready to use it - which is invaluable.

Other reasons AV tech might be bad for Uber include…

AV will make the barrier to entry lower due to improved unit economics, thereby increasing competition within the industry.

The economics of someone else other than Aurora or Uber taking the AV crown may not look so great for Uber.

If proprietary AV tech is founded by another company - there is no guarantee it will be licenced to Uber.

Could AV tech make other public transport more feasible? Meaning less need for taxi-like transport?

So, to summarize, although the introduction of AV could be seen as good or bad for Uber (depending on how it all plays out) the risk/reward ratio is very high. In addition, and just to be clear - this technology is still a long way off being commercially viable. So will Uber be a profitable company before this shift change? Who knows.

4.9. Convergence of assets

Uber has some seriously valuable assets under its belt… two-sided marketplace of drivers and customers, stakes various companies in various industries (Aurora, Joby, Postmates etc..), well known brand, established infrastructure globally and high levles of driver/customer liquidity.

I have mentioned the point before, but one of the beautiful things about Uber, and something you tend not to see directly on the surface, is the synergistic nature of the various arms of operations.

We often hear the term super app batted around - but I think in this case it has a chance at materializing.

5. Market Opportunity

5.1. Mobility Market Opportunity:

For some strange reason, Uber don’t mention much about the development of their Total Addressable Market (TAM) or Servicable Addressable Market (SAM) other than in their original S-1 filing and recent investor presentation, so this is pretty much all we have to go on. Assuming Covid has haulted growth in the industry somewhat, I believe the TAM and SAM calculations will still be more-or-less accurate 3 years on… Just take this data with a pinch of salt.

Defining TAM - “all passenger vehicle miles and all public transportation miles in all countries globally”.

Defining SAM - “all miles traveled in passenger vehicles for trips under 30 miles”

Using the chart above (from the S-1 filing) Uber are telling us it’s still early days in the ride-sharing business - saying the company has only penetrated less than 1% of both the TAM and SAM (SAM = 3.9Tn Miles, Uber = 26billion miles. Therefore 26Bn/3.9Tn = 0.67% penetration). I can’t find any updated version of this stat for 2021.

Realistically, however, I would argue the TAM and SAM are way overstated in order to make the growth opportunity look more attractive than it actually is. I do believe there is significant growth ahead for Uber as they begin to penetrate more and more cities, however Uber and Lyft (and other ride-hailing services) will most likely not be used for most of the journeys under 30 miles.

Why use uber?

Highly liquid service. Due to high demand and supply in larger cities (22% of gross bookings in 2020 came from the top 5 cities), it is an extremely efficient service.

Quick but relatively expensive solution to public transport.

Airports account for over 9% of all trips. Down from 15% in 2018.

Demographics?

Penetration of awareness has increased significantly to nearly 98% of all Americans.

The main demographic is young, well-off people living in large cities where owning a car doesn’t make much sense. Penetration in these demographics is already high (50%-70%)

Is there room to expand?

This is a tricky one. My first reaction would be to lean towards yes due to the constant expansion into new locations. However, competition is rapidly growing meaning companies like Lyft (and Bolt in Europe) are rapidly eating up market share.

The graph above shows 70% of market share. This is correct however still somewhat misleading. According to different sources, market share within the US is somewhere between 65% and 80%, which has come down from 91% in 2015 due to the increase in competition. This number is made up from over 75 million riders and 3.9 million drivers worldwide.

Uber might find it difficult to expand beyond the current user demographics (young people). Once you have children you tend to move outside of cities. Baby seats aren’t easy to come by in Ubers. Etc.

American Automobile Association estimates the cost of owning a car = $0.75 per mile, public transport = $0.27 per mile whilst Uber = $1.6 per mile. Fewer benefits to using an Uber when travelling long distance.

Even with AV’s, people will still own their own cars, therefore not a threat to car ownership.

So, penetration is likely much higher than the 1% mentioned by Uber. TAM and SAM are likely much smaller too. I would lean towards a TAM of roughly $200B with a current penetration (Uber and Lyft) of around 20%-30%.

Some tailwinds such as increasing urbanization and delay in obtaining car licenses do exist and may help expand TAM faster than the broader market, but it is hard to see how these mild long-term tailwinds stem the structural headwinds the ridehailing business faces in penetrating the broader market.

Uber also mentions additions to their mobility segment which refers to modes of transportation such as dockless e-bikes, e-scooters, Transit, UberWorks etc

5.2. Delivery Market Opportunity:

While covid all but decimated the mobility segment, the delivery segment has been thriving. The past 2 years has seen incredible growth as people have been stuck at home - looking for that restaurant experience from the comfort of their living room.

“Of this amount ($2.8Tn in 2017), we believe that our Uber Eats offering addresses a Servicable Addressable Market of $795 billion, the amount that consumers spent in 2017 on meals from home delivery, takeaway, and drive-through worldwide from these consumer food services, including in the 19 countries we address through our ownership positions in our minority-owned affiliates.”

Therefore if we take Uber Eats TTM gross bookings as a percentage of the estimated SAM, penetration currently rests at around 5.5% ($13B/$795B = 1.64%). One massive caveat is we are assuming 0 growth in SAM since this estimate was released over 3 years ago. Realistically, the market has grown considerably over the past 3 years since the S-1 was released.

Considering ‘Eats’ was launched roughly 6 years ago, the growth has been phenomenal in order to reach $13B in quarterly Gross Bookings.

I predict plenty of growth still to come even though we have seen significant pull-forward due to the pandemic. This is evident by the fact that we are starting to see a myriad of competitors enter into the market over the past year as this market continues to boom. E.g. $DASH, $ROO, $DHER…

The above tweet/image is a good example of Uber’s sensible approach to gaining exposure within emerging markets without a heavy-handed tactic of loss-making expansion. They are instead opting to take strategic stakes in local players. This makes Uber well positioned within valuable equity markets without committing too many resources.

Just to add, most of Uber’s ‘profit’ this quarter is comprised of the ‘unrealized gain’ of $1.4B due to having a stake in DiDi and an additional unrealized gain of $471M due to having a stake in Aurora (below).

Delivery, however, is following the same old playbook using aggressive incentive tactics to gain market share. This leaves a big question around long-term profitability.

5.3. Freight

One of Uber’s newer segments is called Uber Freight.

Uber Freight was launched in the US in May 2017. It is a freight brokerage business connecting shippers and carriers i.e. a marketplace to match these two players. According to Armstrong & Associates, the brokerage business is $72 Bn opportunity, which is ~10% of $700 Bn businesses spent on trucking in the US. Considering 2019 bookings, Uber has ~1% market share.

I have already talked about this section above. But regarding future potential - imagine how profitable Freight COULD be if the Aurora bet pays off. They would have an ulimited supply of robo-trucks, virtually 24/7. The unit economics would look great on this.

5.4. ATG

Possibly the hardest to put any real estimate on. The trouble is, no-one knows how close/far autonomous vehicles are to being commercially ready - could be 5 to 10+ years off.

No comment from me on this one.

5.5. Summary of market opportunity

Overall, I’m more skeptical on the future addressable market for mobility. I think there are too many unknowns at this point in time surrounding Autonomous Vehicles, who will use them, what the future of public transport looks like. Additionally, it seems Uber are vastly overstating the TAM & SAM in order to insinuate higher future growth than reality (I could easily be wrong on this). Lastly, it’s super unclear whether the introduction of AV will be a good or bad outcome for Uber - time will tell.

Regarding the ‘Eats’ TAM, I’m much more confident in the long-term growth potential. The market is undeniably large which is shown by the recent influx of companies going public.

Lastly, I like the direction Uber is taking with freight and Autonomous Vehicles/ATG. They both might not be huge markets just yet, but if Uber can continue to solidify themselves in these other large verticals, then the eventual convergence to one ‘Super App’ could be a very real scenario when the day finally comes.

5.6. So what’s next?

Uber’s expansion into food and grocery delivery will position the company to grow into a “super app” revolving around delivery - and it won’t just be food.

The staggering level of optionality within the business is one of the most promising aspects and is something that Lyft/Bolt/Doordash/JustEat don’t have. I strongly believe the route forward is to fully develop each of the upcoming business segments in order to utilize the synergistic nature of their highly liquid two sided marketplaces. The real untapped potential is those vectors converging and compounding.

“Advertising business on Uber Eats is relatively new and high margin (>70% gross) "Our original goal was to exit this year with $100 million of Ads run-rate revenue, but we now expect to surpass that goal and end 2022 with at least $300 million in run-rate revenues."

If we then combine all of the above with Autonomous Vehicles, eVTOL and Transit, you have a holistic door-to-door service which is near impossible for any other company to offer.

“Eventually, you know, I can see a world where if you want to take cash out from the bank, someone will come and deliver cash to you, right? It’ll be anything that you want delivered to your home.” — Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber CEO

Worker rights is still a big issue and one still to be thoroughly played out. I will be watching how this develops closely.

6. Competition

Mobility

Competition is rife within each of Uber’s business segments.

To start with ride-hailing, the main competitor in the US is Lyft who’s market share had grown to roughly 30% over the past several years. Lyft are, I believe, content in being the number 2 ride-hailing service within the market as Uber have done much of the heavy lifting to create the basis of this two-sided marketplace.

Bare in mind that drivers will often drive for both companies. 61% use only Uber while 26% use only Lyft. Uber is also far more prevalent than Lyft outside of the US.

Eats

Since the pandemic the at-home food delivery market has skyrocketed - with some notable acquisitions in the space. Just Eat purchased GrubHub and Uber (after failing to acquire GrubHub) purchased Postmates.

DoorDash remains the largest competitor in the US with 55% market share, up 5% from 1 year ago. uber takes second place with 22% followed by GrubHub with 17% and Postmates with 5%.

Freight

The most direct competition for Uber within this space is Convoy - a Seattle-based startup. “Convoy has raised nearly $668 million in four rounds of funding, according to Crunchbase data.”

“Other competitors to Uber Freight and Convoy include traditional brokers such as publicly-traded giant C.H. Robinson, while freight operators themselves are also investing heavily in technology to keep up with demand. There are also newer direct competitors including Transfix; Trucker Path; DAT; and others.”

Uber Freight is aggressively investing in its algorithms to maintain a competitive edge.

7. Management?

Uber has had an interesting history with CEO’s. The original CEO Travis Kalanick garnered a poor reputation from the media for several fairly damning indiscretions. Here’s a link if you want to read more about it.

Having said that, I believe Travis was crucial in building what is now one of the worlds most influential tech companies. We have to remember Uber were not first to the ride-sharing market - this was Lyft. The only difference between the two were the CEO’s. Travis’s particular skill set (aggressive, scrappy entrepreneur) was likely the major contributing factor in Uber’s success.

All this being said, as Uber evolved over the years, the company culture and management needed to evolve too in order to reflect the improved direction. This lead to Travis’s replacement in 2017 - Dara Khosrowshahi, the previous CEO of Expedia.

CEO: Dara Khosrowshahi (2017-present)

Dara Khosrowshahi offers a completely different leadership style to that of Travis. He has been described as the complete opposite of Travis, who was described as far more aggressive and autocratic in his approach to leadership.

Dara described the situation he inhereted as ‘messy’. He spent the majority of his first year in the job putting out fires, trying to re-build relationships, consulting with employees/engineers/drivers - all of which had become deeply unhappy with the toxic culture.

He has since been instrumental in leading the IPO efforts alongside attracting significant continued investment solidifying the product diversification.

CFO: Nelson Chai (2018-present)

Nelson Chai was appointed as CFO specifically for his IPO-heavy background. Having been handpicked by Dara, he is also an important ally in Uber's notoriously volatile boardroom.

Chai has one of the toughest positions within the company, in that he is responsible for the future profitability of Uber’s famously unprofitable business.

CTO: Sukumar Rathnam (2020-present)

Taking over from Thuan Pham only very recently, Sukumar is responsible for the company’s global engineering organisation.

Prior to joining Uber, Sukumar spent 9 years at Amazon, where he oversaw product management, software engineering, machine learning, and business operations for the selection and catalog systems. These systems manage the world’s largest e-commerce catalog of products and offers, serving up information on billions of products at more than 10M requests/second.

Before Amazon, Sukumar spent many years in software engineering and architecture leadership roles at Microsoft, PeopleSoft, and Oracle.

8. Bull

Optionality – various investments in other ridesharing companies. Other business avenues – advertising. “I would, however, caution that Uber, unlike other big tech, doesn’t have a funding machine such as Search for Google, IG/Big Blue for Facebook, or Prime/AWS for Amazon. Uber’s core business is very much in question which really narrows its capacity to capitalize on its optionality.”

Valuable asset base if the company can sort themselves out.

Large set of proprietary data. Will become very valuable.

Aggregator for all transportation - essentially door-to-door as a service. Having a two-sided network large enough to meet demand/supply needs globally is an incredibly tall order. This advantage, in and of itself, can be a successful Moat. Haulage company’s are a good practical example. U-Haul aren’t the cheapest option – but the availability in every city around the country has enabled them to dominate.

For mobility, Uber has the largest global/U.S. supply and demand network. Riders expect a ride whenever and wherever they are - that requires great supply density. That means many millions of cars ready close by to anywhere the demand may be.

Uber is potentially an "AV agnostic" platform which other robo-taxi services will onboard onto in order to gain sufficient demand. Good plan B in the stake in Aurora.

Uber is the only provider who will be able to offer a holistic AV taxi + eVTOL + transit + eScooter service, meaning they will be the only ones to offer a seamless door-to-door solution.

Skin in the game in each of the above veritcals… Transit = Uber Freight, AV = Aurora, eVTOL = Joby, micro-mobility = Lime.

Offering an incredibly efficient service (most of the time).

9. Bear

Regulations - There has already been many examples of this.

The most high profile example being Prop 22 in California “Uber and Lyft got their way in California with voters supporting their Proposition 22 ballot measure. Prop 22 exempts Uber, Lyft and other app-based transportation and delivery companies from classifying their workers as employees, and lets them keep treating them like independent contractors.”

Big cities are another example of where regulation could easily occurr - majorly effecting Uber’s bottom line. “In 2020, we derived 22% of our Mobility Gross Bookings from five metropolitan areas—Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City in the United States, Sao Paulo in Brazil, and London in the United Kingdom.” It’s not hard to see how the desire for reduced traffic or pollution could result in a crackdown on Uber vehicles in these big cities.

Another example is potential regulation in one of Uber’s top usecases - airport pickups/dropoffs. Parking makes up large rev % at airports, therefore the airports might be incentivised to lobby for regulations.

Competition - Strong competition in all areas. E.g. Lyft in rides.

Loyalty of Drivers/customers - It’s common for drivers to drive for both companies. 61% use only Uber, while 26% use only Lyft.

AV could prove to be the big risk. It’s not clear at all how this will play out in the long-term. It could equally be the best or worst thing to happen to Uber.

Uber product is still very expensive. Car = $0.75 per mile, Uber = $1.6 per mile globally and $2 per mile in the US.

Concerning Unit Economics on each business segment.

Overall revenue growth has been slowing in the recent years - likely to pick back up coming out of Covid.

How long can they keep burning through cash is a very real issue.

10. Financials

10.1. Funding

Uber are well known for the large sums of VC money they have been burning through over the past decade without making any profits. Here are some top level statistics regarding their funding.

Dated Feb 2021:

According to reporting from Crunchbase, “Uber has raised a total of $24.7B in funding over 26 rounds. Their latest funding was raised on Apr 26, 2019 from a Post-IPO Equity round.”

Uber has 107 investors, including PayPal and Toyota Motor Corp.

From August 2015 to January 2020, a grand total of $18.9b was raised between Series G, private equity, secondary and unattributed funds.

There is always going to be an overarching question of whether Uber will ever be able to rectify their cash burning situation. They have roughly $5 billion in cash on the balance sheet along with roughly $15 billion in equity stakes.

I believe Uber have the scale and resources to keep this strategy up for a long, long time.

10.2. Path to profitability or dodgy accounting?

This is a genuine question/concern for Uber. For most of their active life, each business segment has been unprofitable – eats, rides, & other.

The recent investor presentation deck (Q4 2020) shows the company hoping to achieve profitability by the end of 2021. HOWEVER, if we look at what they are actually saying, it looks like they are talking about this mysterious adjusted EBITDA number which, when we look in more detail, seems like a dubious number to use.

Lets dive into this Adjusted EBITDA number in more detail…

As you can see below, Uber outline what they believe should be included in the ‘Non-GAAP’ measure. The problem is, many of the expenses they are adding to the Net income (loss) figure in order to get to this ‘Adjusted EBITDA’ figure should arguably not be added back. The reason being is that these are ongoing costs which you have to pay, they are not one-off expenses.

In the screenshot above, the line items I have marked red I believe should not be included in a classic EBITDA figure as these are ‘real’ costs. * This is debatable, so play around with the numbers to get to your desired EBITDA figure.*

So, taking the above into account, Uber gives us an Adjusted EBITDA figure of $(868)M for the first half of the year, whereas my classic EBITDA figure looks more like $(2,120)M, representing a significant difference in profitability.

Therefore, when we look at Uber’s long-term target of 25% Adjusted EBITDA profitability (as referenced in their investor deck) we can adjust by our new EBITDA figure to find the ‘real’ profitability level.

The above table basically shows that, if we take into account our new number for EBITDA instead of relying on their adjusted EBITDA figure, which was previously a target of 25% ‘adjusted EBITDA’ profitability - it turns out to be only 6.7% classical EBITDA profitability - a big difference.

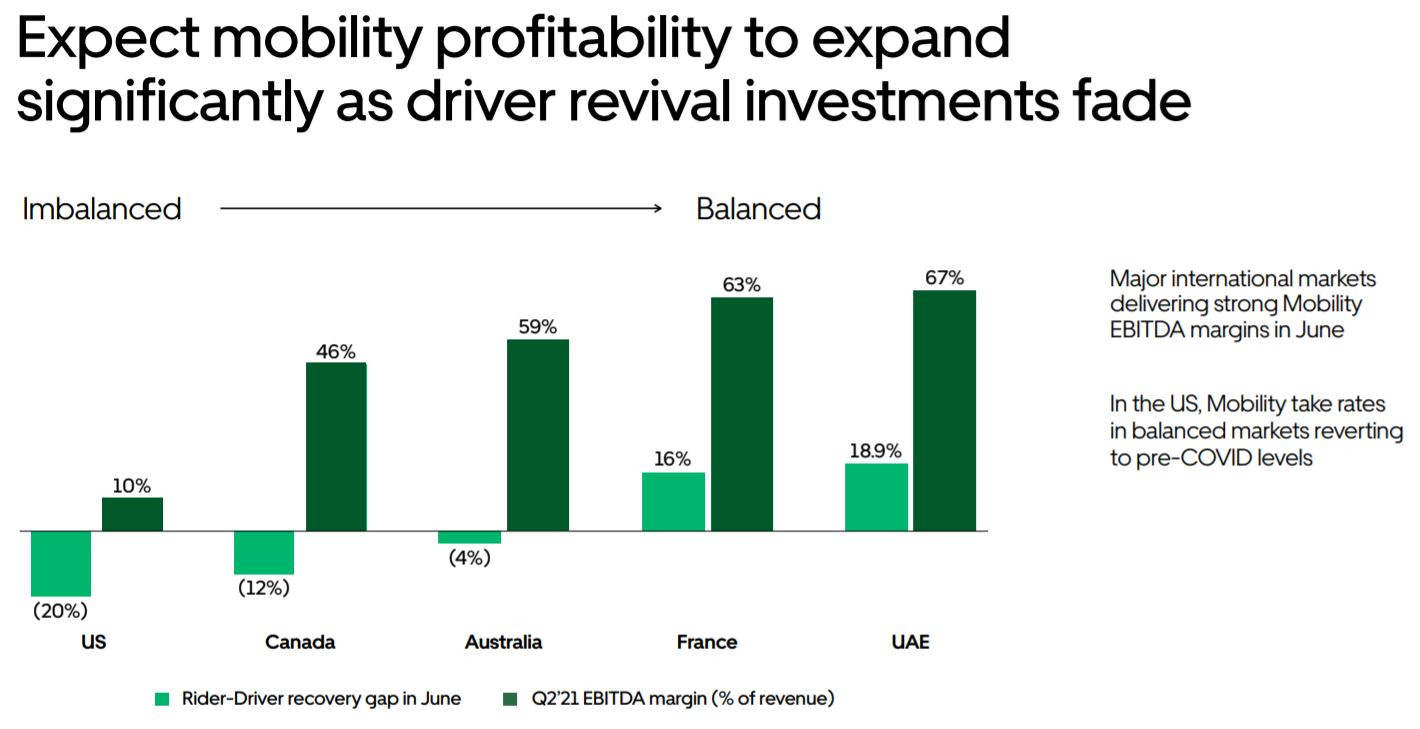

We have seen some relative profitability in other regions in recent quarters…

June has seen EBITDA look extremely positive.

“in major markets like Australia, Canada, France, and UAE where supply was organically recovering without significant investments from Uber, our Mobility EBITDA margin in Q2 exceeded long-term targets, ranging from 46% to 67% of revenue.”

The goal is to achieve quarterly adjusted profitability sometime in 2021. This has been majorly impacted by the pandemic – however it’s hard to say whether it’s a meaningful goal in and of itself due to the ambiguity around what the ‘profitability’ number actually encompasses.

10.3. Operating leverage

As alluded to earlier, Uber’s cost structure is unique in that they have very few fixed costs to worry about - they don’t own the cars or bikes drivers use to make trips. This means improving the cost structure might be tricky due to the majority of their costs being variable. Lets look at how they can improve these costs.

Cost of revenue primarily consists of certain insurance costs related to our Mobility and Delivery offerings, credit card processing fees, bank fees, data center and networking expenses

So what can Uber change here?

Insurance costs - This is a complex aspect, and not something I’m super knowledgeable about. However, knowing Uber primarily buys insurance from third parties, they could look to bring this aspect more in-house. That being said, I think it would be best to leave the insurance companies to do what they do best.

Driver incentives - These incentives are crucial for eating up market share and remaining competitive over the short-to-medium term. Realistically, we can expect a taper-off over the long-term as Uber capture the wider ridesharing and delivery market.

Payment processing - is currently roughly 20% of the total cost of revenues and around 2% of total gross bookings. I believe this is likely to stay proportional as scale continues, therefore no massive opportunities to reduce costs here.

Operations and support - This mainly consists of “compensation expenses, including stock-based compensation, for employees that support operations in cities, including the general managers, Driver operations, platform user support representatives and community managers. Also included is the cost of customer support, Driver background checks and the allocation of certain corporate costs.”

One aspect that jumps out as a potential improvement in operating leverage is the driver background checks. If Uber can reduce the current high-level of driver churn in the system, we could see some non-trivial savings. For reference, a study from 2015/16 showed 68% of drivers stopped driving within 6 months. This may have improved recently, but I couldn’t find any evidence. The reason for this high level of churn is likely due to the nature of the business - oftentimes drivers use uber as an inbetween job with no real intention of it being a long-term career.

Sales and Marketing - Mainly consists of “compensation costs, including stock-based compensation to sales and marketing employees, advertising costs, product marketing costs and discounts, loyalty programs, promotions, refunds, and credits provided to end-users who are not customers, and the allocation of certain corporate costs.”

This cost represented roughly 31% of total revenue in 2020 and has a run-rate percentage of 35% in 2021. Realistically, instead of rising I would be looking to see this number come down to ~20% of revenue in order for the company to be looking at strong profitability.

Having said this, I’m not sure how easy it will be for Uber to lower this cost if promotions and incentives become an integral part of the business. I.e. what happens if they stop offering the incentives to improve short term profitability?

R&D - Mainly consists of “compensation costs, including stock-based compensation, for employees in engineering, design and product development.” It used to include a significant portion devoted to R&D on the ATG programme, however since the deal late last year, this expense item has decreased dramatically - from ~24% of Revenue to ~15% of revenue.

You might argue if Uber want to be competitive in the AV space then a higher allocation here would be prudent, however I believe they have structured the deal with Aurora in a way that allows for both a reduction in R&D whilst remaining competitive.

10.4. Income statement

Lets first look at Uber’s finances from a distance, then I will delve deeper into individual aspects I find interesting.

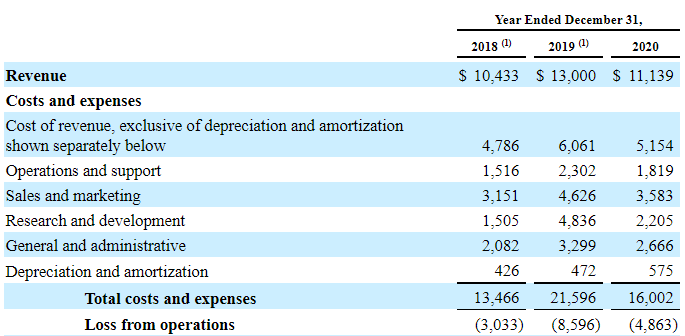

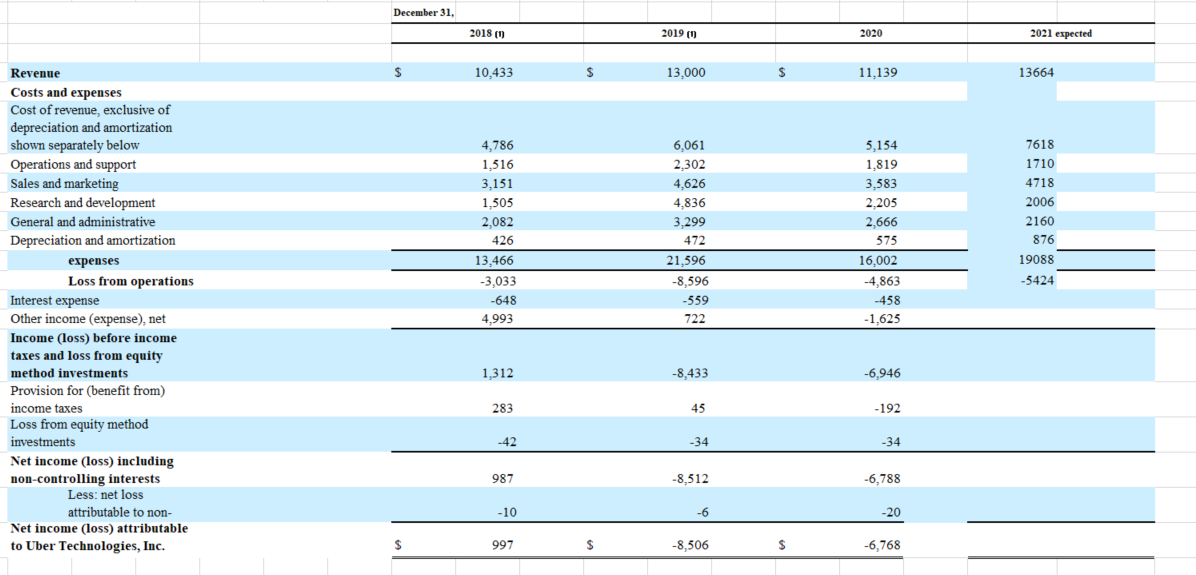

Firstly, if we do some general trend analysis of Uber over the past few years, the picture doesn’t look too rosy.

We can see revenue is generally increasing over the years as the company continues to grow and expand into new markets/territories. Then looking down just one line we can see the gross margin figure (cost of revenue) equates to roughly 50% of sales in most years. Not too bad so far.

Below the cost of revenues are the other costs necessary to run the business. In this case, after these extra costs are applied, we’re looking at a net loss of between 30% and 60%. If we then consider the recent change in classification of Uber drivers in the UK to workers (not quite employees), we have to ask the question will this increase costs over time as the administrative burden of on-boarding these workers increases?

10.5. Balance Sheet

Current assets = $$7,783M

Total Asssets = $36,251M

Current liabilities = $7,684M

Total liabilities = $20,507M

The main thing to point out here is the total equity number, which has increased over the past couple of years. This is mainly due to the additional paid in capital number, some of which derives from the redeemable convertible preferred stock figure, but the remainder is the result of a significant injection of cash from investors. Therefore, the cash has been increasing over the years.

In addition, the company’s total assets easily cover the current & total liabilities which is a healthy position to be in long-term. The one negative is the fact that total liabilities outweigh current assets by roughly 3X. This indicates some level of risk if some of this longer-term debt needed to be paid off in the short-term.

10.6. Cash Flows

The cash flow situation for Uber is far from healthy at first glance - having never produced positive cash flows from operations. From the image above we can see Uber burn a frankly ridiculous amount of cash - as high as 4.2B in 2019. It doesn’t take much to get slightly worried that if Uber continue this pattern of burning cash over a long period of time, investors might end up pulling out.

Ideally, over the next 3-5 years I would expect to see this figure turn positive as some of these markets start to mature and Uber figure out a way to be profitable.

Historically, as we can see, the main source of cash for the business has been through financing activities which, in the long run, could be unsustainable.

Most notable, however, is the recent rise in cash flows from investing activities which has popped up into the positives at $101M. This is mainly due to the appreciation in value of the various investments Uber is exposed to.

10.7. Valuation

In order to come up with a suitable valuation for Uber, I decided to base my calculations on my classical EBITDA figure in the profitability section above (6.7%). The reason being is that this is their long-term target for profitability. 10 years seems like a good amount of time to achieve this.

*These calculations involve many assumptions which you might disagree with. Feel free to play around with the numbers*

Firstly, based on the past revenue growth (2017 to 2021 run rate) we end up with an average revenue growth of 18%. For simplicity, I decided to round this figure up to 20% moving forwards.

Secondly (left table) I forecast revenue over the next 10 years, to 2031 using this flat growth rate of 20%. This ends up being $117B. Once we have this revenue figure, we can then work out the estimated EBITDA from our calculations earlier (6.7%) to give us an EBITDA in 2031 of $7.8B.

After this, we have enough information to come to an estimated stock price.

A few more assumptions have to be made. I have slapped on a 20X market multiple (which seems fair) to get us to an Enterprise Value of $157B.

Take away debt (5% of EV in this case) gets us to a Market Cap of $149B. We then divide $149B by the number of outstanding shares to get a predicted stock price in 2021 of $79.24.

This indicates a potential upside of 85% or a CAGR of 6.38%.

On a relative EV to Sales basis, Uber comes out at 6.9X, sitting nicely in the middle of big tech, other food delivery and other ride-sharing companies.

*For those of you who have made it this far, thank-you! Please consider a small donation if you enjoyed the article as it helps me out massively.*

11. Conclusion

This is possibly one of the toughest conclusions I have had to write. On one hand, I’m looking at a company that, on paper, is hemorrhaging money. There is literally no evidence they are capable of posting a profit. And even when they do, it’s a manufactured (very dubious) ‘Adjusted EBITDA’ figure. The risk/reward ratio is not the best in this case.

On the other hand, I’m an optimist. I see a company who have changed the world, and in doing so have put themselves in prime position to capitalize on multiple growing market. Not only that, but the convergence of these markets could easily be a case where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

With relatively new management looking to change the direction of the company and several positive recent quarters, Uber is beginning to catch my eye.

Long-term (and I mean at least 5-10 years minimum) Uber could be the most dominant delivery/transport technology company in the world - or not. I’ll leave that for you to decide.

Cheers,

Innovestor